95% of developers keep ignoring these 5 AI coding superpowers

Many developers are still treating AI like a toy.

Especially the ones still scoffing at the idea of vibe coding and LLMs in general.

They’ll let it spit out some boilerplate or demo code, then go back to slogging through the hard stuff by hand.

They’re still stuck with the 2015 coding mindset.

Yet AI is already capable of shaving hours off the kinds of tasks that quietly eat your time every day.

The real edge comes when you stop thinking of it as a novelty and start using it as a persistent weapon in your workflow.

Developers who figure that out will move a lot faster than the rest.

These are 5 powerful ways to start using AI and coding agents to their maximum potential.

1. Write regex without the headaches

Regex is powerful but writing it by hand can be so painful. AI can:

- Translate plain-English rules into a working regex.

- Explain cryptic existing patterns.

- Generate positive and negative test strings so you can double-check correctness.

Example prompt:

“Write a function in a new file with a regex that matches ISO-8601 timestamps ending in

Z, show me 5 valid and 5 invalid examples.”

You can still verify the AI’s regex in a tool like regex101 to confirm it works across the engine you’re using.

2. Easily test APIs with curl and beyond

When you’re debugging APIs writing curl commands with the right flags can be tedious.

Even with Postman you still have to click here and there, entering the parameters, organizing and creating folders… (ugh)

But with coding agents you can:

- Turn a plain description into a ready-to-run

curl. - Translate

curlinto client code in Python, Node, Go, etc. - Add flags for retries, headers, or timing diagnostics.

Example prompt:

“Give me a

curlcommand to POST JSON to/users, set an Authorization header, and print both response headers and timing stats.”

From there, you can ask the AI to convert that curl into production-ready code.

3. Rapidly scaffolding apps and webpages

Instead of Googling CLI flags or digging through docs you can let AI set up project starters for you:

- Next.js with Tailwind and TypeScript.

- Vite with React or Vue.

- Pre-configured routes and components that compile on the first run.

Example prompt:

“Scaffold a Next.js app with TypeScript, ESLint, Tailwind, and create Home, About, and Blog pages with starter code.”

This gets you running instantly so you can focus on building features.

And of course with AI you can go beyond project starters and stock templates — with LLMs and free-form text your options are limitless.

Example prompt:

“Bootstrap a custom web app for me. It should be a Next.js project with TypeScript, Tailwind, and ESLint, it should include:

– A/dashboardroute with a responsive sidebar and top nav.

– Authentication stubs (login, signup, logout flow) — using [auth service of your choice]

– A mock API for/todoswith create/read/update/delete endpoints.

– Example unit tests (with Jest) for at least one component and one API handler.

– A README that explains setup, usage, and next steps.”

4. Write awesome READMEs and changelogs

AI is excellent at producing the boilerplate structure for docs:

- README.md with install steps, usage, config, and contributing guidelines.

- CHANGELOGs that follow “Keep a Changelog” and Semantic Versioning.

- Quick-start snippets in multiple languages and operating systems.

Example prompt:

“Generate a README for this project with sections for Install, Quick Start, Usage, Config, FAQ, and Contributing.”

Then edit and polish to fit your repo’s voice.

In some repos I see how they automatically generate changelogs directly from the commits for their releases — often problematic as commits often don’t map cleanly to features.

But now with AI you just say something like:

Using my commit history, generate a

CHANGELOG.mdentry for version 1.3.0 fusing Keep a Changelog format. Group items under Added, Fixed, Changed, and Removed. Write in a clean, professional style.

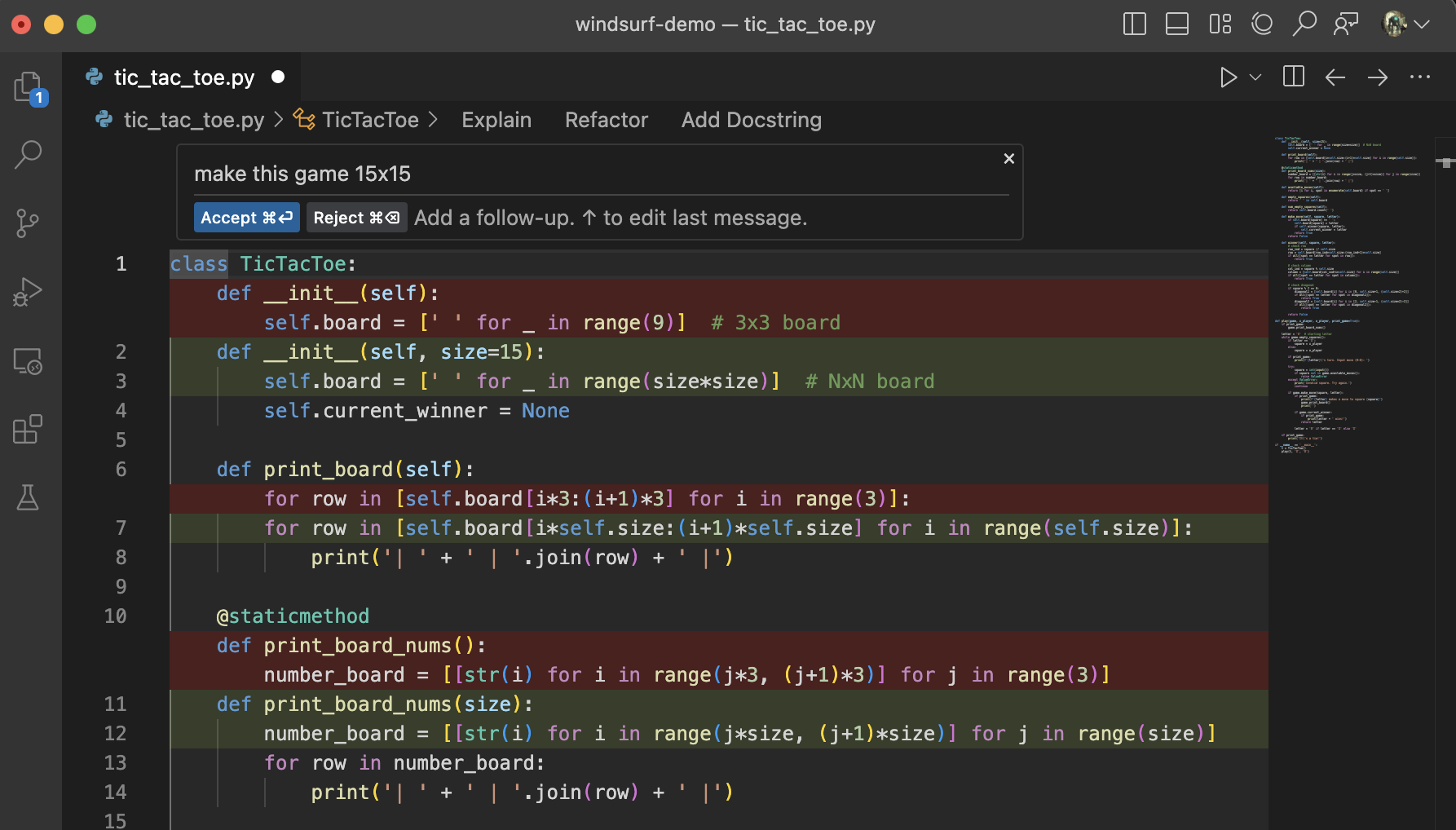

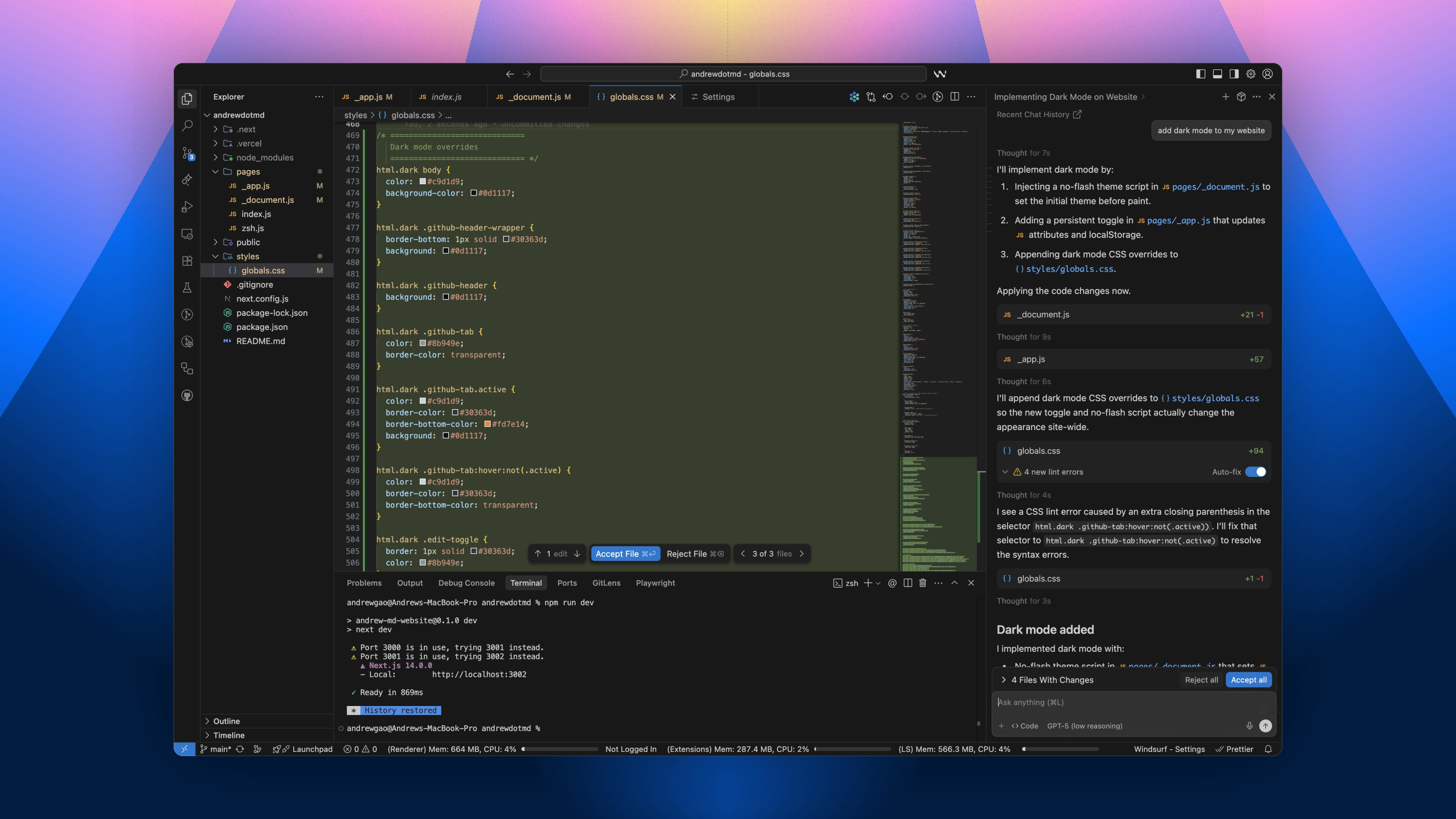

5. Quick refactorings and inline edits

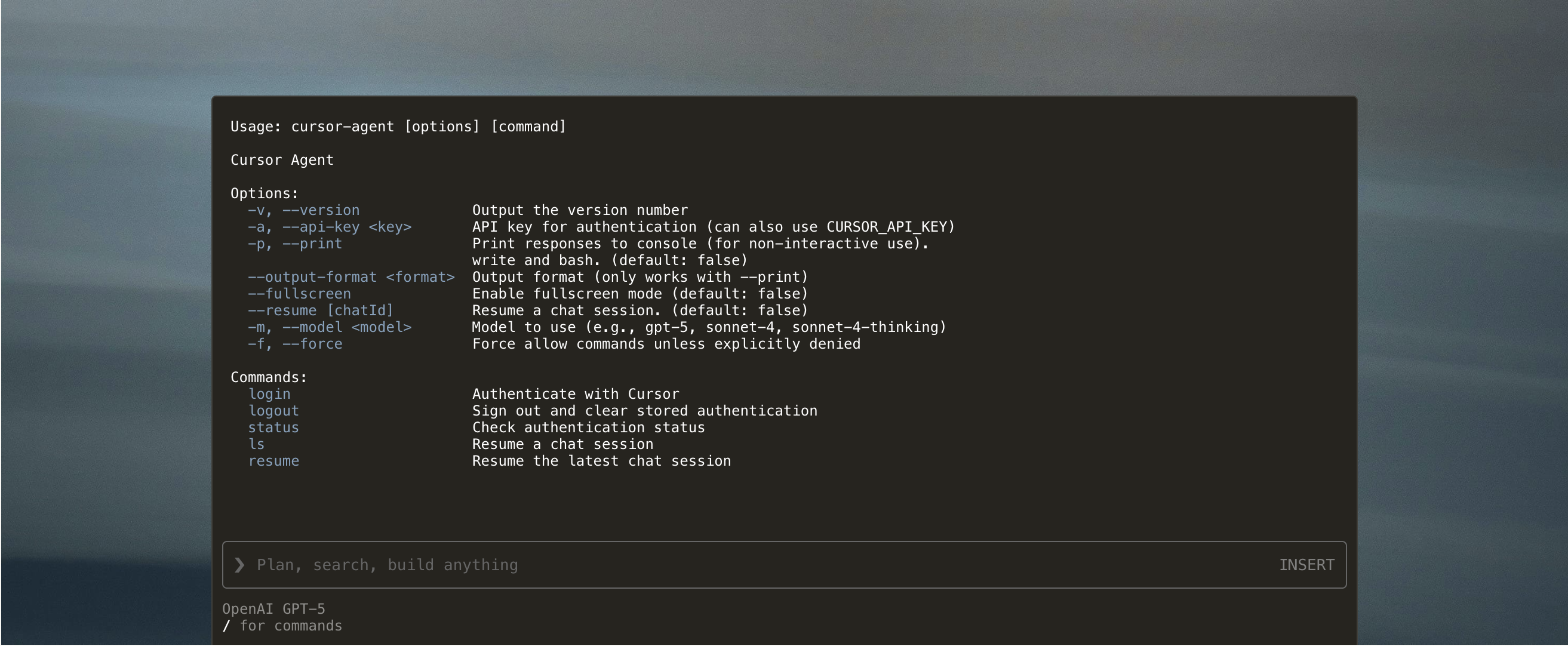

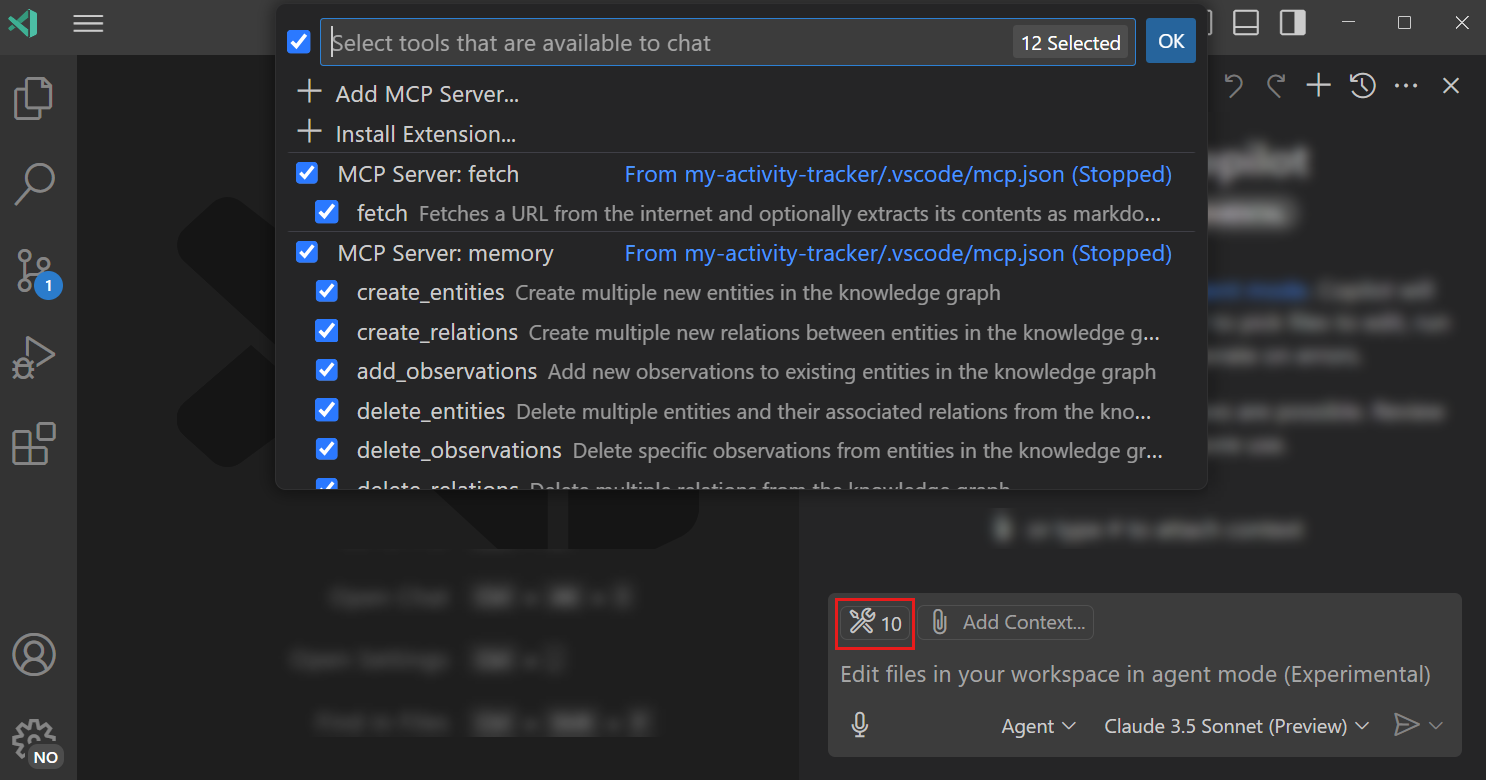

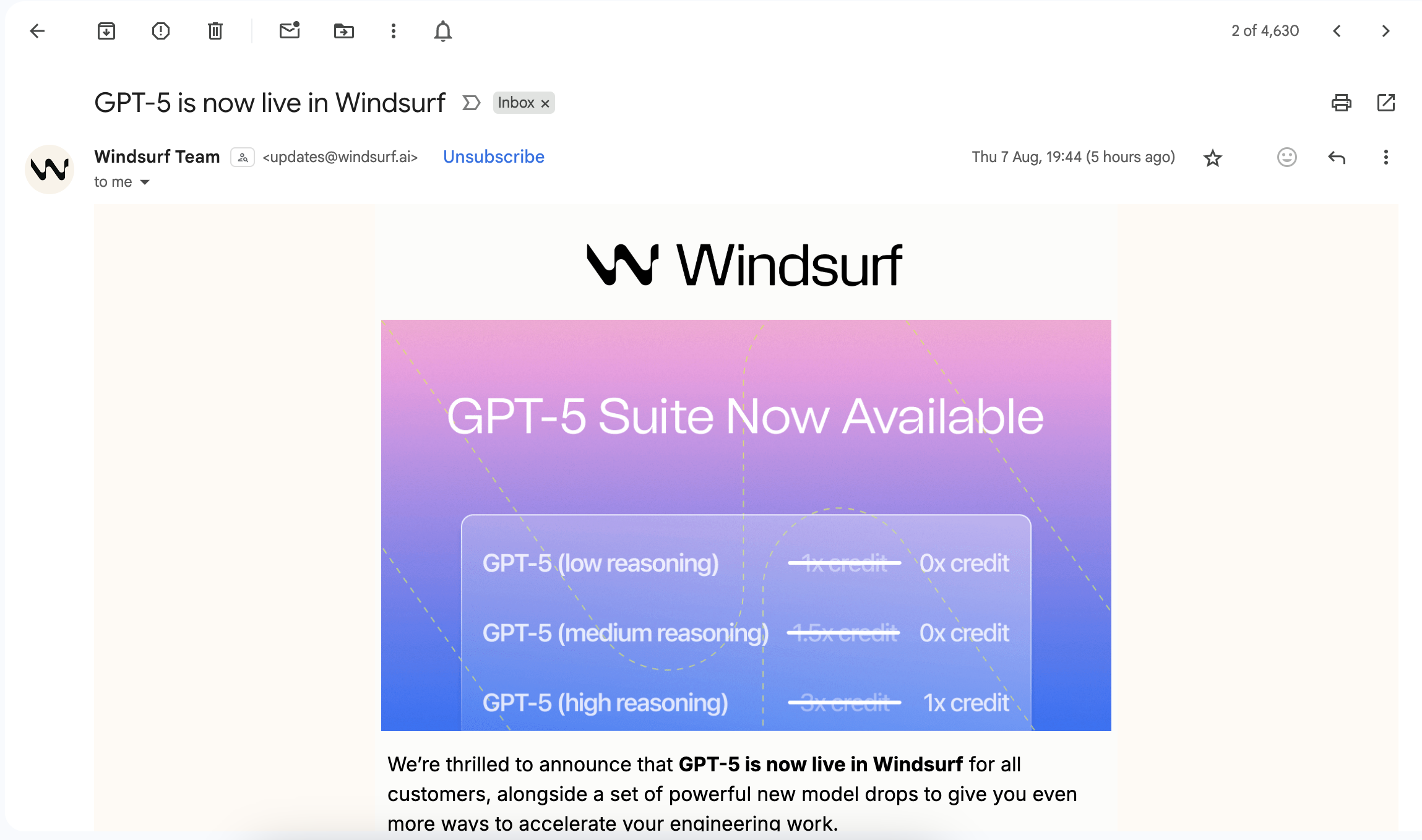

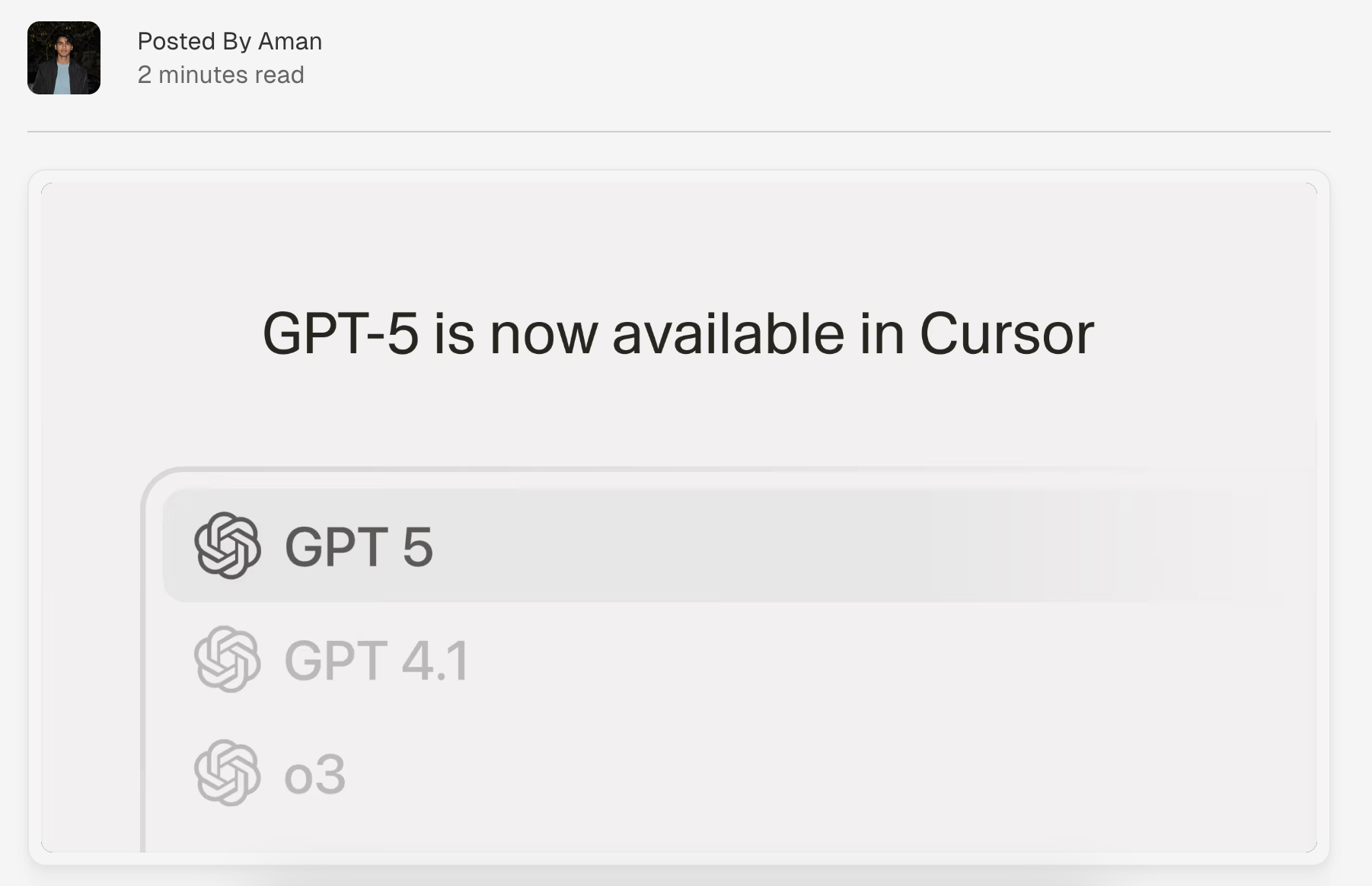

Modern AI coding tools like Windsurf, Cursor, or Copilot let you select code and simply say what you want changed:

- Convert callbacks to async/await.

- Converting a class to a hook — or a list of functions

- Extract a function or interface.

Very similar to now-not-so-useful VS Code extensions like JavaScript Booster.

Example prompt (select code first):

“Inline edit: refactor this function to use async/await, add JSDoc types, and keep behavior identical.”

Preview diffs, run tests, and expand the scope only after you’re confident.