How to write “natural” code everybody will love to read

The biggest reason we use languages like JavaScript and Python instead of Assembly is how much closer to natural language they are.

Or how much they CAN be!

Because sometimes we write code just for it to work without any care about demonstrating what we’re doing to other humans.

And then this backfires painfully down the line. Especially when one of those humans is your future self.

Parts of speech: back to basics

You know your code is natural when it resembles English as much as possible. Like an interesting, descriptive story.

It means you’ve intelligently made the entities and actions in the story to powerfully express the code flow from start to completion.

Nouns

What entities are we talking about?

- Variables

- Properties (getters & setters)

- Classes & objects.

- Modules

Every character has a name, so we describe them with expressive nouns and noun phrases.

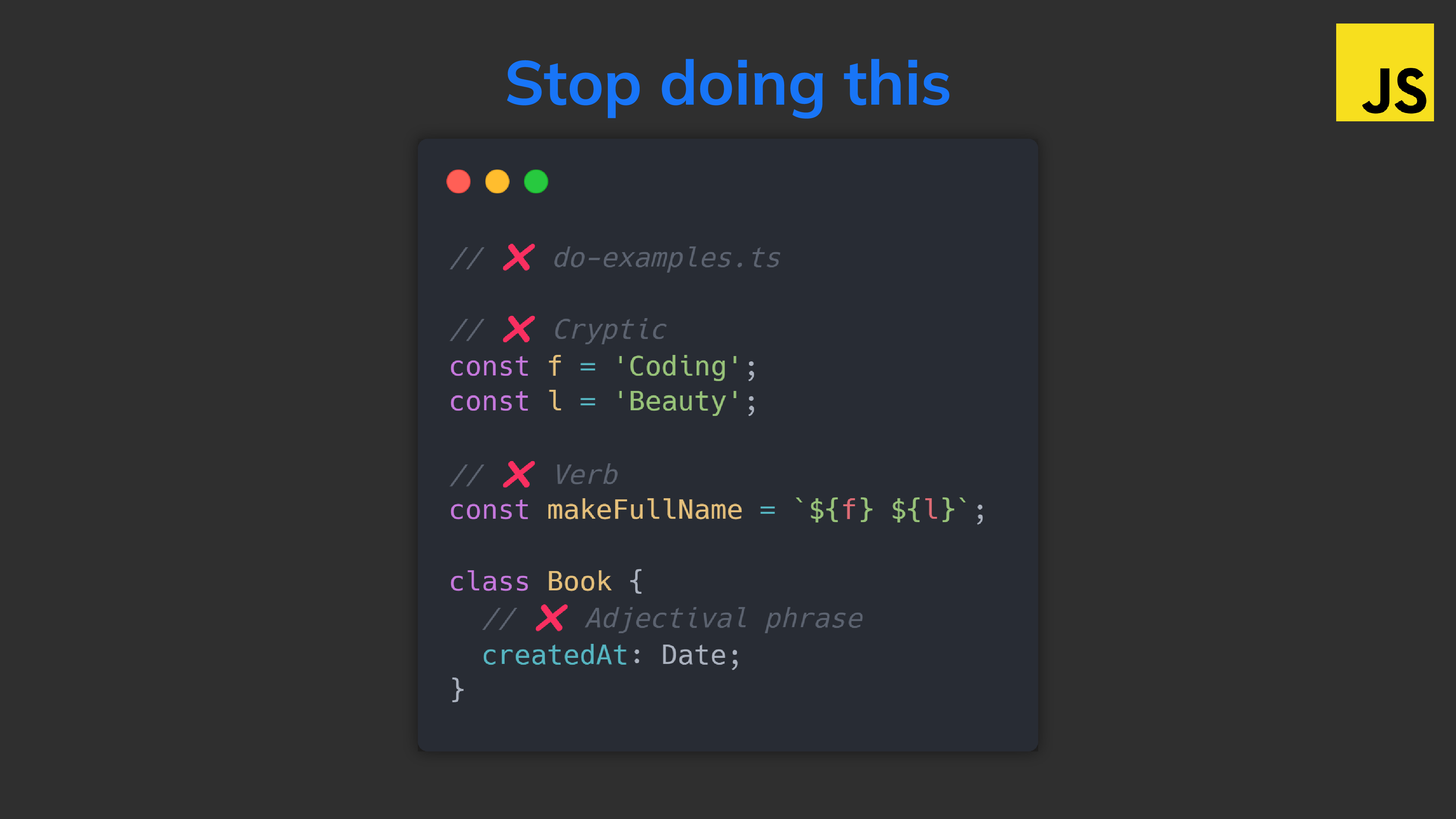

Not this:

// ❌ do-examples.ts

// ❌ Cryptic

const f = 'Coding';

const l = 'Beauty';

// ❌ Verb

const makeFullName = `${f} ${l}`;

class Book {

// ❌ Adjectival phrase

createdAt: Date;

}But this:

// ✅ examples.ts

// ✅ Readable

const firstName = 'Coding';

const lastName = 'Beauty';

// ✅ Noun

const fullName = `${firstName} ${lastName}`;

class Book {

// ✅ Noun phrase

dateCreated: Date;

}Verbs

What are the actions in your codebase?

- Functions

- Object methods

An action means an entity is doing something; the naturally way to name them is with descriptive verbs and verb phrases.

Not this:

class Product {

constructor(name, price, quantity) {

this.name = name;

this.price = price;

this.quantity = quantity;

}

// ❌ Noun

total() {

return this.price * this.quantity;

}

}

const product = new Product('Pineapple🍍', 5, 8);

console.log(product.total()); // 40But this:

class Product {

constructor(name, price, quantity) {

this.name = name;

this.price = price;

this.quantity = quantity;

}

// ✅ Verb

getTotal() {

return this.price * this.quantity;

}

}

const product = new Product('Banana🍌', 7, 7);

console.log(product.getTotal()); // 49Methods are for doing something. Properties are for having something.

So better still:

class Product {

constructor(name, price, quantity) {

this.name = name;

this.price = price;

this.quantity = quantity;

}

get total() {

return this.price * this.quantity;

}

}

const product = new Product('Orange🍊', 7, 10);

console.log(product.total); // 70Adverbs

Remember an adverb tells you more about a noun or verb or another adverb.

In JavaScript this is any function that takes function and returns another: a higher-order function. They upgrade the function.

So instead of this:

// ❌ Verb

function silence(fn) {

try {

return fn();

} catch (error) {

return null;

}

}

const getFileContents = (filePath) =>

silence(() => fs.readFileSync(filePath, 'utf8'));

It’ll be more natural to do this:

// ✅ Adverb

function silently({ fn }) { // or "withSilence"

try {

return fn();

} catch (error) {

return null;

}

}

const getFileContents = (filePath) =>

silently({ fn: () => fs.readFileSync(filePath, 'utf8') });It’s like saying, “Get the file contents silently“.

Natural inputs

Coding and computing are all about processing some input to produce output.

And in natural code the processing is action and the input + output are entities.

Let’s say we have a function that calculates a rectangle’s area and multiplies it by some amount.

Can you see the problem here?

const area = calculateArea(2, 5, 10); // 100Which argument is the width and height? Which is the multiplier?

This code doesn’t read naturally; In English we always specify objects of an action.

How to fix this? Named arguments:

// Inputs are entities - nouns✅

const area = calculateArea({ multiplier: 2, height: 5, width: 10 });

function calculateArea({ multiplier, height, width }) {

return multiplier * height * width;

}This is far easier to read; we instantly understand what inputs we’re dealing with.

Even when there’s just 1 argument I recommend using this.

Natural outputs

And we can be just as explicit in our outputs:

const { area } = calculateArea({

multiplier: 2,

height: 5,

width: 10,

});

function calculateArea({ multiplier, height, width }) {

return { area: multiplier * height * width };

}Which also allows us easily upgrade the function later:

const { area, perimeter } = calculateArea({

multiplier: 2,

height: 5,

width: 10,

});

console.log(area, perimeter); // 100 60

function calculateArea({ multiplier, height, width }) {

return {

area: multiplier * height * width,

perimeter: (height + width) * 2 * multiplier,

};

}There’s no time for magic

Coding isn’t a mystery thriller! It’s a descriptive essay; be as descriptive as possible.

Not this cryptic mess:

function c(a) {

return a / 13490190;

}

const b = c(40075);

console.log(p); // 0.002970677210624906What do all those numbers and variables mean in the bigger picture of the codebase? What do they tell us – the human?

Nothing. They tell us nothing. The entity & action names are either non-existent or of terrible quality.

It’s like telling your friend:

Yeah I went to this place and did this thing, then I did something to go to this other place and did something of 120!.

This is nonsense.

Natural code describes everything. Nice nouns for entities, great verbs for the actions.

const speedstersSpeedKmPerHr = 13490190;

const earthCircumferenceKm = 40075;

function calculateSpeedstersTime(distance) {

return distance / speedstersSpeedKmPerHr;

}

const time = calculateSpeedstersTime(earthCircumferenceKm);

console.log(time); // 0.002970677210624906 ~ 11sNow you’ve said something.

Yeah I went to the restaurant and ate a chicken sandwich, then I drove to the gym and did bicep curls of 120 pounds!.

Create “useless” variables

Variables in natural code are no longer just for storing values here and there.

They’re also tools to explain what you’re doing:

That’s why instead of doing this:

if (

!user.isBanned &&

user.pricing === 'premium' &&

user.isSubscribedTo(channel)

) {

console.log('Playing video...');

}We’ll do this:

const canUserWatchVideo =

!user.isBanned &&

user.pricing === 'premium' &&

user.isSubscribedTo(channel);

if (canUserWatchVideo) {

console.log('Playing video...');

}

We’re going to use the variable only once but it doesn’t matter. It’s not a functional variable but a cosmetic variable; a natural variable.

Final thoughts

Code is for your fellow humans too, not just compilers.

Can someone who doesn’t know how to code understand what’s going on in your code?

This is no doubt a powerful guiding question to keep your code as readable an natural as possible.