Google I/O was completely insane for developers

Google I/O yesterday was simply unbelievable.

AI from head to toe and front to back, insane new AI tools for everyone — Search AI, Android AI, XR AI, Gemini upgrades…

Developers were so so not left behind — a ridiculous amounts of updates across their developer products.

Insane coding agents, huge model updates, brand new IDE releases, crazy new AI tools and APIs…

Just insane.

Google sees developers as the architects of the future and this I/O 2025 definitely proved it.

The goal is simple: make building amazing AI applications even better. Let’s dive into some of the highlights.

Huge Gemini 2.5 Flash upgrades

The Gemini 2.5 Flash Preview is more powerful than ever.

This new version of their top model is super fast and efficient, with improved coding and complex reasoning.

They’ve also added “thought summaries” to their 2.5 models for better transparency and control, with “thinking budgets” coming soon to help you manage costs. Both Flash and Pro versions are in preview now in Google AI Studio and Vertex AI.

Exciting new models for every need

Google also rolled out a bunch of new models, giving developers more choices for their specific projects.

Gemma 3n

This is their latest open multimodal model, designed to run smoothly on your phones, laptops, and tablets. It handles audio, text, images, and video! You can check it out in Google AI Studio and with Google AI Edge today.

Gemini Diffusion

Get ready for speed! This new text model is incredibly fast, generating content five times quicker than their previous fastest model, while still matching its coding performance. If you’re interested, you can sign up for the waitlist.

Lyria RealTime

Imagine creating and performing music in real-time. This experimental model lets you do just that! It’s available through the Gemini API.

Beyond these, they also introduced specialized Gemma family variants:

MedGemma

This open model is designed for medical text and image understanding. It’s perfect for developers building healthcare applications, like analyzing medical images. It’s available now through Health AI Developer Foundations.

SignGemma

An upcoming open model that translates sign languages (like American Sign Language to English) into spoken language text.

This will help developers create amazing new apps for Deaf and Hard of Hearing users.

Fresh tools to make software dev so much easier

Google truly understands the developer workflow, and they’ve released some incredible tools to streamline the process.

A New, More Agentic Colab

Soon, Colab will be a fully “agentic” experience. You’ll just tell it what you want, and it will take action, fixing errors and transforming code to help you solve tough problems faster.

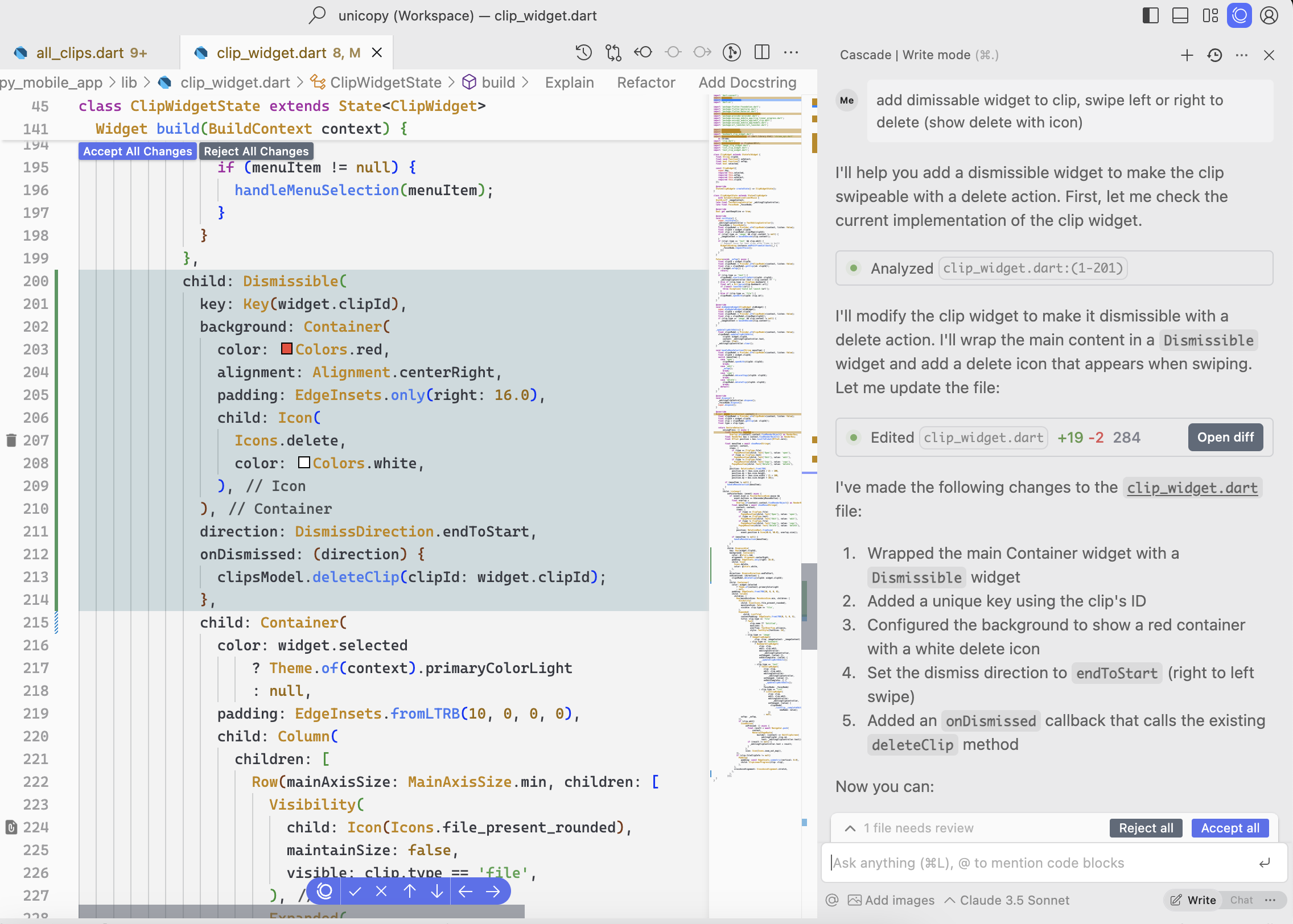

Gemini Code Assist

Good news! Their free AI-coding assistant, Gemini Code Assist for individuals, and their code review agent, Gemini Code Assist for GitHub, are now generally available. Gemini 2.5 powers Code Assist, and a massive 2 million token context window is coming for Standard and Enterprise developers.

Firebase Studio

The official unveiling after replacing Project IDX.

This new cloud-based AI workspace makes building full-stack AI apps much easier.

You can even bring Figma designs to life directly in Firebase Studio. Plus, it can now detect when your app needs a backend and set it up for you automatically.

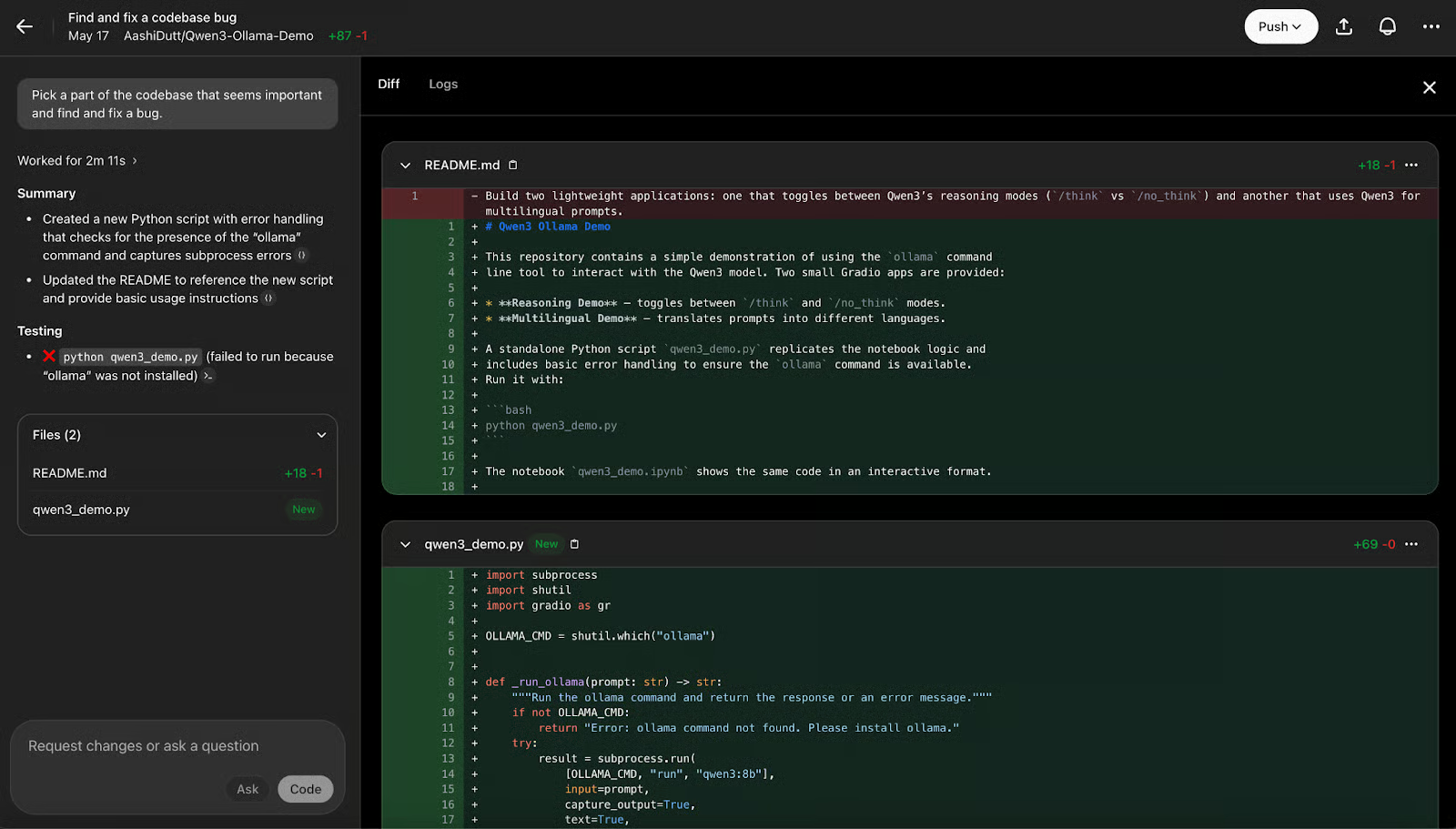

Jules

Now available to everyone, Jules is an asynchronous coding agent. It handles all those small, annoying tasks you’d rather not do, like tackling bugs, managing multiple tasks, or even starting a new feature. Jules works directly with GitHub, clones your repository, and creates a pull request when it’s ready.

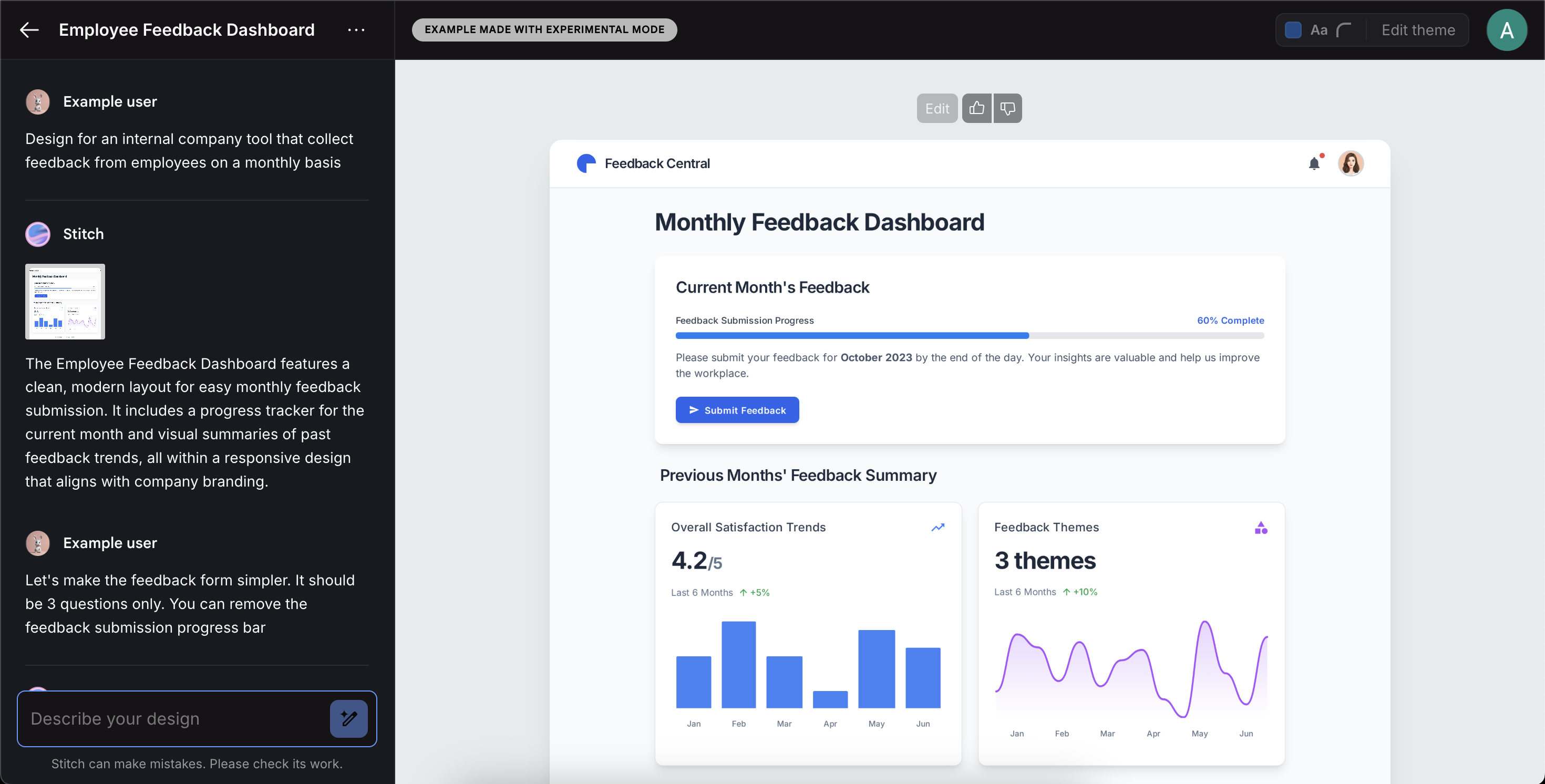

Stitch

This new AI-powered tool lets you generate high-quality UI designs and front-end code with simple language descriptions or image prompts. It’s lightning-fast for bringing ideas to life, letting you iterate on designs, adjust themes, and easily export to CSS/HTML or Figma.

Powering up with the Gemini API

The Gemini API also received significant updates, giving developers even more control and flexibility.

Google AI Studio updates

This is still the fastest way to start building with the Gemini API. It now leverages the cutting-edge Gemini 2.5 models and new generative media models like Imagen and Veo. Gemini 2.5 Pro is integrated into its native code editor for faster prototyping, and you can instantly generate web apps from text, image, or video prompts.

Native Audio Output & Live API

New Gemini 2.5 Flash models in preview include features like proactive video (detecting key events), proactive audio (ignoring irrelevant signals), and affective dialogue (responding to user tone). This is rolling out now!

Native Audio Dialogue

Developers can now preview new Gemini 2.5 Flash and 2.5 Pro text-to-speech (TTS) capabilities. This allows for sophisticated single and multi-speaker speech output, and you can precisely control voice style, accent, and pace for truly customized AI-generated audio.

Asynchronous Function Calling

This new feature lets you call longer-running functions or tools in the background without interrupting the main conversation flow.

Computer Use API

Now in the Gemini API for Trusted Testers, this feature lets developers build applications that can browse the web or use other software tools under your direction. It will roll out to more developers later this year.

URL Context

They’ve added support for a new experimental tool, URL context, which retrieves the full page context from URLs. This can be used alone or with other tools like Google Search.

Model Context Protocol (MCP) support

The Gemini API and SDK will now support MCP, making it easier for developers to use a wide range of open-source tools.

Google I/O 2025 truly delivered a wealth of new models, tools, and API updates.

It’s clear that Google is committed to empowering devs to build the next generation of AI applications.

The future is looking incredibly exciting!